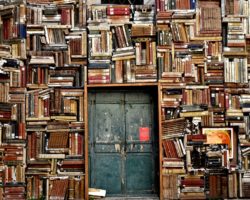

Simon Alexander was the sort of man who left the library with a volume of Pushkin, Churchill’s The Gathering Storm, Ultimate Spider-Man Vol. 10, A Brief History of Time, and “G” is for Gumshoe, and returned them a week later, each read cover to cover. The library could not keep up with his voracious appetite.

He learned calculus online and Photoshop as well. He took piano lessons and Russian lessons and etiquette lessons. He read the dictionary and old encyclopedias and church cookbooks. He tore apart cars and clothes to see what held them together. He studied the Bible and Der Ring des Nibelungen and on vacation wandered through the Louvre for a week.

Sometimes he stopped along the sidewalk and picked a weed and wondered what its name was and how it grew and where it originated and whether you could eat it. At night he would look at a star and wonder at its course and its size and how he could learn to use a sextant.

He grew in wisdom, delighted with knowledge and the hidden threads that connected the Black Death to the creation of pubs and California drought to the start of the X Games.

He was delighted but unhappy. If he read Tang Dynasty poetry, he had no more time for French existential plays. If he visited a nearby town looking for some U.S. Geological Survey benchmarks, his ignorance of local housing ordinances continued.

Books only got him so far. To read was to open a box, but the box was bottomless and filled with facsimiles, with cunningly wrought miniatures of the real thing. But to look up from a book was to drown. When Simon Alexander stepped outside his house, the avalanche buried him.

That’s why he built the time machine.

The trick with time machines is that they take as much skill at carpentry as at quantum mechanics, and nearly as much Art Deco as Brutalism. Simon possessed just the right concoction of philosophical nuance and dime novel moralism to fold space-time and just enough historical knowledge of the past and science fiction fear of the future to keep it in a box. It was a long, thin box when he finished, with a lid that lifted and just enough room for him to lie down and shut himself in.

In an instance, he fell through time–to the French Revolution, of course, and to ancient Egypt; to the beginnings of Babylon and of Beatlemania. He spent a quiet night in Nepal and a stormy noon in New Zealand. He floated amid endless ocean and trekked through deserted urban landscapes. Back and forth he went through time and space, like a kid in a candy store, like a man searching for his lost child, like an old man’s words recounting the old days.

Then, one day, his long, narrow, black box landed upon the moon. He sat up and looked upon the Earth in her majesty and despaired. He envied the men and women down there, the ones who fathered and mothered, who fought and healed, who tilled and taught, those who spent their few years on bees or organ repair or cataloging railway routes. Simon Alexander knew they did not know what they did not know, but he knew also that they knew what they knew and were happy–and he was not. He was famished, bitter, cynical, and sad.

It was then, as he beheld the world and everything in it, that the answer came to him. Simon knew that the universe expanded, that time moved ever forward, that after page one came page two and page twenty-two million. But there was a page one.

He lay back in his metal box and dialed it back to the beginning, from which all things flowed and from whence came all knowledge.

His box rattled and shook and fell silent. Out of the darkness he emerged into light, into air that shone and land that blazed green, and he looked, and there he saw an apple, and he saw that it was pleasing to the eye and desirable for gaining wisdom. And so he took it and he ate it.